Where Locals Actually Go

The spots that don't show up on "Best Of" lists

Fargo-Moorhead has a visitor center with a woodchipper photo op. It has a downtown walking tour. It has all the obvious stuff. What it doesn't advertise are the places locals actually get excited about—the weird shops tucked inside other shops, the archives nobody knows exist, the statues everyone drives past without noticing. This is the other Fargo.

1

NDSU Archives Off-Site Facility

In a nondescript industrial warehouse on Seventh Avenue North—the former Knox Lumber Company building—sits one of the region's most overlooked historical treasures. Heavy boxes of original glass plate negatives from the late 1800s through the 1930s capture early NDSU campus life: students in wool coats squinting at the camera, buildings that no longer exist, a prairie campus before it sprawled. The collection nearly vanished 25 years ago when it was stored in a basement that flooded. Now it lives in climate-controlled obscurity, available to anyone who calls ahead but unknown to almost everyone. The lead archivist puts it simply: "A lot of people don't realize this is available." They don't. Most locals have no idea it exists. That's the point.

2

Tiny Things

North Dakota's smallest store is exactly what it sounds like: a shop that sells only tiny things, housed in a space barely bigger than a closet. It's tucked inside Brewhalla, a craft beer market on First Avenue North, which means you have to know it exists to find it—and even then, you might walk past twice. The inventory is miniature jewelry, tiny prints, small gift baskets, and an assortment of quirky objects scaled for dollhouses or people who like their possessions pocket-sized. Atlas Obscura featured it. The owners open 360+ days a year, which in Fargo weather is a commitment. The whole thing feels like a joke that turned into a business that turned into a legitimate destination. In a land of big sky and endless horizons, someone decided to go the opposite direction entirely.

3

The Rourke Art Gallery + Museum

Most visitors to Fargo-Moorhead head straight for the Plains Art Museum. The Rourke, across the river in Moorhead, gets overlooked—which is a mistake. Housed in a 1915 Federal Courthouse building, the collection started as one man's obsession and stayed that way. James O'Rourke spent decades acquiring art that interested him personally, with no curatorial mandate to follow. The result is a "wonderfully unexpected array": ancient Asian artifacts next to pre-Columbian pottery, European prints beside regional work, religious icons sharing walls with contemporary pieces. It doesn't make sense by museum standards. It makes sense as one person's vision of what matters. The building itself—with its high ceilings and federal gravitas—adds a layer of formality that the eclectic collection cheerfully ignores. Free admission. Limited hours. Almost no one you meet in Fargo will have been there.

Sponsored Pick

Advertisements help support our content

4

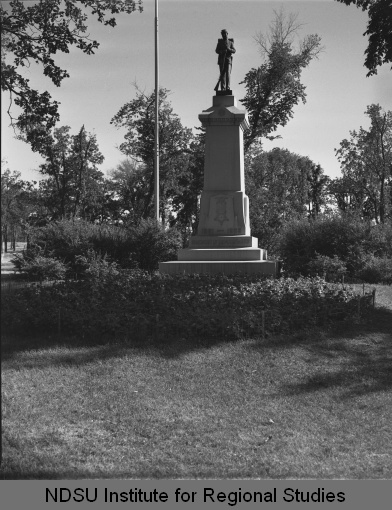

Island Park's Forgotten Monuments

Island Park is where Fargo jogs and picnics and lets the dog run. It's also where two statues stand almost completely ignored. The first is a Grand Army of the Republic Civil War soldier—one of the few Civil War monuments in North Dakota, a state that didn't exist during the war and sent no regiments. Why is it here? Veterans who settled the prairie after Appomattox brought their memorials with them. The statue faces east, toward battlefields most Fargo residents have never thought about. A hundred feet away stands Henrik Wergeland, the "father of Norwegian literature," cast in bronze by the legendary sculptor Gustav Vigeland. It's identical to the one in Oslo. Wergeland was part of Norway's independence movement, and after 1905, Norwegian-American communities erected monuments to prove they hadn't forgotten. Most Fargo residents have walked past both statues without noticing. Most couldn't tell you who Wergeland was. The monuments outlast the memory.

5

Fargo Forest Garden

In 2008, volunteers ripped up a vacant lot's concrete. In 2009, they planted a forest. Not a park—a forest garden, designed on permaculture principles: fruit trees, berry shrubs, perennial vegetable guilds, plants that feed each other and the neighborhood. It's a certified Audubon backyard bird habitat, which sounds official but really just means the birds figured out something good was happening here. The space is intentionally wild-looking, tucked into a corner of northeast Fargo where nobody would expect an urban food forest to exist. Most people who live nearby don't know it's there. The ones who do treat it like a secret—a place to sit, read, sketch, or just be somewhere that isn't a parking lot. The Urban Farm Collective maintains it. The city mostly ignores it. That's probably why it still feels like a discovery.

Stay curious

New stories and hidden gems delivered to your inbox.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Explore More

Discover more curated guides and local favorites.

Fargo's Best Bars

Dive bars, cocktail lounges, and neighborhood favorites

Explore

Fargo's Best Restaurants

From fine dining to hidden gems and local favorites

Explore

Fargo's Best Coffee Shops

Local roasters, cozy cafes, and third wave spots

Explore

Fargo's Dark History

Unsolved mysteries and darker chapters

Explore

Fargo's Curiosities

Fascinating facts and surprising stories

Explore

Fargo's Lost & Loved

Beloved places we miss

Explore

Phoenix Best Bars

Dive bars, cocktail lounges, and neighborhood favorites

Explore

Phoenix Best Coffee Shops

Local roasters, cozy cafes, and third wave spots

Explore

Know something we missed? Have a correction?

We'd love to hear from you