At 9:14 PM on November 22, 1987, Chicago sportscaster Dan Roan was wrapping up the sports segment on WGN-TV's 9 o'clock news. He was talking about the Bears. Then his face disappeared.

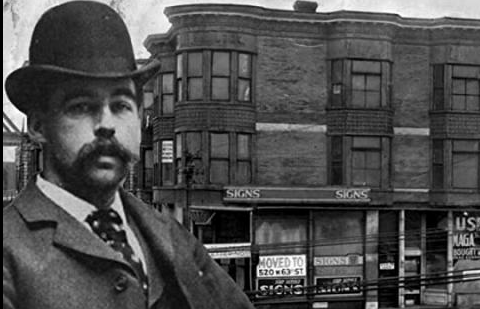

For about 25 seconds, viewers saw something else: a figure in a rubber mask, swaying back and forth against a spinning corrugated metal background. The mask was unmistakable — it was Max Headroom, the computer-generated TV character who'd become a pop culture phenomenon. There was no sound, just a harsh electronic buzzing. Then, as suddenly as it appeared, the image vanished and Dan Roan was back, looking confused.

"Well, if you're wondering what's happened," Roan said, "so am I."

The Mask

Max Headroom was everywhere in 1987. The character — a supposedly computer-generated TV host played by actor Matt Frewer — had started as a British music video presenter, spawned a dystopian TV movie, and then an American TV series. He appeared in Coca-Cola commercials. He was on magazine covers. His stuttering, glitching delivery and sharp-angled face were instantly recognizable.

So when someone wearing a Max Headroom mask appeared on Chicago television that night, viewers knew immediately what they were seeing. What they didn't know — what nobody knows to this day — is who was behind the mask, or why.

The Second Intrusion

The WGN incident might have been dismissed as a technical glitch. But two hours later, it happened again — this time on WTTW, Chicago's PBS station, during a broadcast of the British science fiction show Doctor Who.

This time, there was sound. And what viewers heard was deeply strange.

The figure in the Max Headroom mask appeared against the same corrugated metal background, but now they were talking — or trying to. The audio was distorted, like it was being run through a synthesizer. The voice droned and slurred. The figure swayed erratically, making bizarre statements that seemed to mean nothing.

What They Said

The figure's statements included references to WGN sportscaster Chuck Swirsky ("I just made a giant masterpiece for all the greatest world newspaper nerds"), the cartoon Clutch Cargo ("My brother is wearing the other one"), and the Coca-Cola slogan "Catch the Wave." Near the end, the figure moaned, bent over, and was spanked with a flyswatter by an unseen accomplice. Then the transmission ended.

The whole thing lasted about 90 seconds. Then Doctor Who resumed as if nothing had happened. But something had happened — something that would obsess investigators, broadcasters, and internet sleuths for decades.

How They Did It

What the hijackers accomplished was technically impressive. In 1987, TV signals traveled from studios to broadcast towers via microwave links. To override a broadcast, you had to aim a more powerful microwave signal at the tower than the station was sending — and you had to do it from somewhere in the tower's line of sight.

The equipment required was substantial: a high-powered microwave transmitter, a properly tuned antenna, and extensive knowledge of broadcast frequencies and FCC regulations. This wasn't something you could do with off-the-shelf electronics. The hijackers either had professional broadcasting experience or access to someone who did.

WGN's engineers managed to retake their signal after about 25 seconds by switching to a backup transmission link. But WTTW had no engineers on duty at their transmitter that night — they couldn't respond. The hijackers had ninety uninterrupted seconds to do whatever they were doing.

"He's obviously versed in broadcast engineering... he knew how to override the signal."

— FCC Official, Investigation report, 1987

The Investigation

The FCC and FBI launched an immediate investigation. Broadcasting without a license was a federal crime. Hijacking someone else's signal was worse. If caught, the perpetrators faced serious prison time.

WTTW offered a reward for information. Investigators interviewed broadcast engineers across the Chicago area. They examined the footage frame by frame, looking for clues in the background, in the audio, in anything that might identify the location or the people involved.

They found nothing. The corrugated metal background revealed nothing about the location. The distorted voice couldn't be matched to anyone. The cultural references — Chuck Swirsky, Clutch Cargo, Coke commercials — seemed random. The investigation went cold.

Nobody ever came forward. Nobody claimed credit. The FBI eventually closed the case, unsolved.

The Theories

In the decades since, amateur investigators have proposed countless theories. Disgruntled TV engineers. Phreakers — phone hackers — showing off their skills. College students from Northwestern or UIC pulling an elaborate prank. Performance artists making a statement about media manipulation.

In 2010, a Reddit user claimed to know who did it — supposedly members of a Chicago hacker community in the 1980s. The claim was never verified. Other leads have surfaced over the years, all of them inconclusive.

The most likely explanation is the most mundane: someone with broadcast engineering skills and a grudge against WGN (the references to Chuck Swirsky suggest the hijackers had specific beefs with the station) decided to make a point. They succeeded beyond their wildest dreams — and were smart enough to never get caught.

Why It Matters

The Max Headroom incident is the only broadcast signal intrusion in American history that remains completely unsolved. It's also almost impossible to replicate today — the switch from analog to digital broadcasting in 2009 made the technique used in 1987 obsolete. It was a crime uniquely suited to its moment in technological history.

The Creep Factor

What makes the Max Headroom incident so enduring isn't the technical achievement — it's the footage itself. There's something deeply unsettling about it. The swaying figure. The distorted voice. The rubber mask with its frozen grin. The spanking at the end, childish and inexplicable.

It feels like a transmission from somewhere else — like the hijackers were trying to communicate something, but whatever they wanted to say got lost in translation. Or maybe there was no message. Maybe the incoherence was the point.

The footage circulates endlessly online, rediscovered by each new generation. It's been analyzed, parodied, and memed. It shows up in "creepy unsolved mysteries" compilations. Something about it refuses to become ordinary, no matter how many times you watch it.

On November 22, 1987, somebody hijacked Chicago television. They wore a rubber mask. They made no sense. They got away with it. The FBI gave up. The statute of limitations has long since expired. Whoever did it could confess tomorrow and face no legal consequences.

But they never have. For almost forty years, they've kept their secret. Maybe they're dead. Maybe they forgot. Or maybe they're still out there, watching the footage go viral again and again, knowing they pulled off something nobody else ever managed: a crime that became a legend, committed by ghosts who were never caught.

Catch the wave.

Watching the Footage

The complete footage of both broadcast intrusions is widely available on YouTube and internet archives. Search for "Max Headroom incident" or "Max Headroom broadcast intrusion." Warning: many viewers find the footage genuinely disturbing.