Beyond the Seward Highway

Anchorage's abandoned missile sites, spirit houses, and a 20-foot chocolate waterfall

Most visitors come for the mountains and glaciers. The secrets worth finding are the Cold War bunkers tucked into the hillsides, the floatplane bases where bush pilots drink their morning coffee, and the windowless dive bars where the real Alaska hides from cruise ship crowds.

1

Nike Site Summit

At the height of the Cold War, Anchorage sat directly in the crosshairs of Soviet bombers flying over the pole—so the U.S. Army built a ring of nuclear-armed missiles around the city. Nike Site Summit, perched atop Mount Gordon Lyon at 4,500 feet, was part of this "Ring of Steel" from 1959 to 1979. The missiles are long gone, but the concrete bunkers, launch pads, and control buildings remain frozen in time—one of the most complete Nike Hercules sites left in America. Tours (offered through Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson) take you through barracks where soldiers waited for orders that never came, past empty silos that once held weapons capable of destroying formations of Soviet aircraft, and along ridges with views of the city those weapons were meant to protect. The site feels like a time capsule from an era when nuclear war felt inevitable and Anchorage was ground zero.

Mount Gordon Lyon12.5 miles east of downtown

Tours only through Joint Base Elmendorf-Richardson

Varies by tour

2

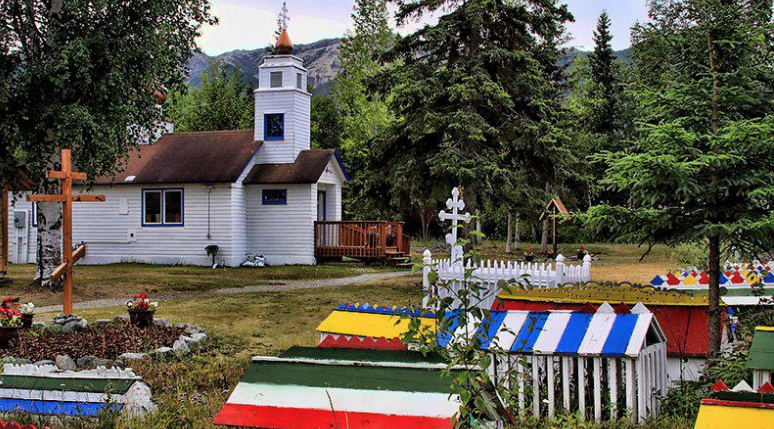

Eklutna Spirit Houses Cemetery

Twenty-five miles north of Anchorage, at the oldest continuously inhabited site in the region, over 100 brightly painted spirit houses stand among the birch trees—a tradition that exists nowhere else on Earth. When Russian Orthodox missionaries arrived in the 1800s, the Dena'ina Athabascan people merged their burial practices with the new faith: bodies are buried with blankets in the Orthodox tradition, but 40 days later, families build small wooden spirit houses over the graves, painted in clan colors that identify family lines. Per Athabascan tradition, the houses are left to decay naturally—new wood standing next to weathered predecessors going back generations. The adjacent St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Church, built in 1870, is the second-oldest building in Anchorage. This is sacred ground, still used for burials today, and visitors are welcome to witness a tradition that bridges centuries and cultures.

St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox ChurchEklutna Village (25 miles north)

Open daily

Small donation appreciated

3

Earthquake Park

On Good Friday 1964, the ground shook for four and a half minutes. The 9.2-magnitude earthquake—the second most powerful ever recorded—devastated Anchorage, and nowhere more dramatically than Turnagain Heights, where an entire bluff liquefied and slid into Cook Inlet, taking 75 homes with it. The bodies were never recovered; the ground was too unstable to search. Today, Earthquake Park preserves the landslide zone, and sixty years later, you can still see what happened: rippling hills, sudden drops, and terrain that looks like it was stirred by a giant spoon. The destruction is frozen in time, overgrown with grass and birch but unmistakably wrong. Interpretive signs tell the story of the families who lost everything in minutes. On clear days, you can see Denali from the overlook—beauty and catastrophe occupying the same view.

Sponsored Pick

Advertisements help support our content

4

Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center

Seeing Alaskan wildlife in the wild is never guaranteed—bears might be fishing elsewhere, moose might be browsing out of sight, caribou might be a hundred miles north. The Alaska Wildlife Conservation Center offers a guarantee: orphaned and injured animals, unable to survive in the wild, living out their lives where visitors can see them up close. The brown bears are the stars, but the moose, musk oxen, caribou, wolves, and porcupines each have their own enclosures spread across the facility. This isn't a zoo—it's a rescue center that happens to allow visitors. The animals have space, the presentations are educational rather than performative, and the drive to get here (45 minutes south, along Turnagain Arm) is one of the most scenic in America. For visitors with limited time who want a guaranteed wildlife encounter, this is the answer.

5

Little Lithuanian Museum

In a tiny yellow house in Chugiak, Svaja Worthington runs what might be the most personal museum in Alaska. Svaja's family fled Lithuania when the Soviets invaded in 1944; she was four years old. The artifacts she displays—traditional clothing, family photographs, handwritten letters, folk art—are her family's possessions, carried through refugee camps across Europe before finally arriving in Alaska. The museum also serves as the Honorary Consulate of Lithuania, which means Svaja is both the curator and the closest thing to an ambassador within a thousand miles. She guides every visitor herself, telling stories that connect the objects to the history they represent. It's not a museum in the institutional sense—it's a woman sharing her family's survival with anyone curious enough to ask.

6

Alaska Law Enforcement Museum

Alaska didn't become a state until 1959, and before that, law enforcement in the territory was... creative. This 3,000-square-foot museum downtown traces that history through the objects officers carried and criminals encountered: a 1952 Hudson Hornet patrol car restored to showroom condition, wire-tapping equipment from the bootlegging era, territorial badges from before anyone agreed on what Alaska even was, antique radios that connected officers across distances that would take days to cross. The shackles are unnerving. The vintage uniforms are surprisingly dapper. The stories—gold rush justice, Prohibition-era smuggling, bush pilots doubling as lawmen—feel like they belong in novels. Alaska's only law enforcement museum sits quietly downtown, passed by tourists who don't know it exists, guarding artifacts from an era when the law had to improvise.

245 W 5th Avedowntown Anchorage

WebsiteWed-Fri 10am-4pm, Sat 12-5pm (closed Sun-Tue)

$5 ($3 for military, law enforcement, youth, seniors)

Sponsored Pick

Advertisements help support our content

7

Campbell Creek Gorge Overlook

Anchorage is full of people who've lived here for years without knowing that a 200-foot canyon cuts through the Chugach foothills ten minutes from downtown. The Campbell Creek Gorge Overlook is unmarked, unimproved, and unknown to most—a tree-shrouded ledge where you look straight down at whitewater crashing through a slot canyon that feels transplanted from the Southwest. The trail to reach it isn't on most maps; you have to know which fork to take from the Hillside Ski Chalet parking lot. Stand at the edge and the city feels impossibly far away—just rushing water, sheer rock, and the kind of silence that makes you understand why people move to Alaska and never leave.

8

Glen Alps Aurora Viewpoint

When the aurora forecast goes active, half of Anchorage drives to the same crowded pullouts on the Glenn Highway. The other half—the ones who know—drive to Glen Alps. At 2,200 feet, above the city lights and facing north toward the Alaska Range, this Chugach State Park trailhead offers what might be the best aurora viewing within reach of the city. Five mountain ranges ring the horizon. The Anchorage Bowl glitters below. And when the lights come—green curtains rippling across the sky, sometimes pink, sometimes purple—you watch from a parking lot that feels like a front-row seat to the universe. Dress for genuine cold. Arrive before dark to claim a spot. And check the aurora forecast before driving up—when it's active, the parking lot fills with photographers, champagne toasts, and Alaskans who never get tired of watching the sky.

9

Ship Creek Urban Salmon Viewing

In most cities, a creek running through downtown is a sad afterthought. In Anchorage, Ship Creek fills with thousands of salmon every summer—king salmon in May and June, silvers from July through September—and you can watch them fight upstream from viewing platforms a ten-minute walk from the hotel district. The fish ladders and spillway at the William Jack Hernandez Sport Fish Hatchery give you close-up views of salmon in their final, desperate push to spawn. Better yet, you can fish: Ship Creek is one of the best urban salmon fishing spots in America, and you can rent gear on-site if you didn't bring your own. The Alaska Railroad rumbles past on schedule. Eagles circle overhead. The whole scene feels impossibly Alaskan, and it's hiding in plain sight downtown.

Ship Creek Overlook ParkEast Whitney Road

WebsiteOpen daily; best July-September

Free (fishing license required to fish)

Sponsored Pick

Advertisements help support our content

10

Turnagain Arm Bore Tide

Twice a day, during extreme tides, a wall of water up to ten feet high comes thundering into Turnagain Arm at speeds up to 24 mph—one of the largest bore tides in North America. The physics are dramatic: a 40-foot tidal swing funnels into a narrow, shallow arm, compressing into a wave that advances for miles. Local surfers ride the bore for distances that would be impossible in ocean surf. Kayakers paddle frantically to stay ahead of it. From the viewing point at Beluga Point, you watch the wave approach like a freight train made of water, churning the silty inlet white as it passes. The bore tide happens on a schedule dictated by the moon, strongest during new and full moons, most dramatic around the fall equinox. Miss the timing and you'll see nothing. Nail it and you'll witness one of Alaska's most surreal natural phenomena.

Best viewing: Beluga Point (20 min south of Anchorage)

WebsiteCheck tide charts; arrive 30 min before predicted arrival

Free to view

11

World's Largest Chocolate Waterfall

Inside an unassuming candy factory south of downtown, a 20-foot waterfall of molten chocolate cascades through three tiers of vintage copper candy kettles—over 3,000 pounds of chocolate in continuous flow. Homer artist Mike Sirl built this confectionary monument in 1994, and while Guinness has never officially certified it, no one has stepped forward to claim a larger one. You can't drink from it (health codes being what they are), but you can stand and watch chocolate fall in sheets while contemplating the glorious absurdity of building something like this in Alaska, of all places. The surrounding store sells wild berry products, fudge, and tourist kitsch, but the waterfall is the draw. It's free to view, delightfully weird, and exactly the kind of thing that shouldn't exist but does.

12

Anchorage Light Speed Planet Walk

A high school astronomy student designed this: a scale-model solar system stretching from downtown Anchorage to the Kincaid Park chalet, with the Sun at 5th and G Street and Pluto 5.5 hours away on foot. The brilliance is in the math—if you walk at a casual pace, you're moving at the speed of light relative to the model. Earth is an eight-minute walk from the Sun. Jupiter takes 45 minutes. By the time you reach Pluto, you've covered miles of Anchorage's best trail system and gained an intuitive understanding of just how empty and vast the solar system actually is. Most people don't walk the whole thing. Most people don't need to. Just walking from the Sun to Mars will change how you think about space.

Sponsored Pick

Advertisements help support our content

13

Oscar Anderson House Museum

Anchorage didn't exist until 1915. That year, the Alaska Railroad began construction, and a tent city sprang up at Ship Creek to house the workers. Oscar Anderson claimed to be the 18th person to arrive—he kept count. The wood-frame house he built that summer is now Anchorage's only historic house museum, restored to its 1915 appearance and designated a National Trust Distinctive Destination. Anderson went on to become one of early Anchorage's most prominent citizens: meat packer, coal dealer, aviation pioneer, newspaper owner. His house sits in Elderberry Park, steps from the coastal trail, a reminder that this city of 300,000 began barely a century ago with a railroad, a handful of tents, and people like Oscar Anderson who saw opportunity in the wilderness. The 45-minute tours are led by docents who know the stories that don't make the history books.

14

Indigenous Place Names Project Markers

Before Anchorage was Anchorage, it was Dena'ina land—and the Dena'ina Athabascan people had names for every creek, inlet, and mountain. The Indigenous Place Names Project is slowly restoring that language to the landscape: 32 sculptural markers now stand along Anchorage trails and parks, each featuring a Dena'ina place name, its English translation, and the story behind it. Artist Melissa Shaginoff designed the markers to incorporate traditional fire bag patterns and contemporary Indigenous art. Each one reads "You are walking on Dena'ina land"—a simple statement that reframes the city around you. Find them at Westchester Lagoon, Muldoon Park, Potter Marsh, Point Woronzof, and along the Chester Creek trail system. The project is ongoing; new markers appear regularly.

Stay curious

New stories and hidden gems delivered to your inbox.

No spam. Unsubscribe anytime.

Explore More

Discover more curated guides and local favorites.

Anchorage's Best Bars

Dive bars, cocktail lounges, and neighborhood favorites

Explore

Anchorage's Best Restaurants

From fine dining to hidden gems and local favorites

Explore

Anchorage's Best Coffee Shops

Local roasters, cozy cafes, and third wave spots

Explore

Anchorage's Darkness at the Edge

Unsolved mysteries and darker chapters

Explore

Anchorage's Curiosities

Fascinating facts and surprising stories

Explore

Anchorage's Lost Anchorage

Beloved places we miss

Explore

Tampa Best Bars

Dive bars, cocktail lounges, and neighborhood favorites

Explore

Tampa Best Restaurants

From fine dining to hidden gems and local favorites

Explore

Know something we missed? Have a correction?

We'd love to hear from you