Mile High Hustle

Gold, silver, oil, weed, and the peculiar alchemy of turning mountain proximity into money

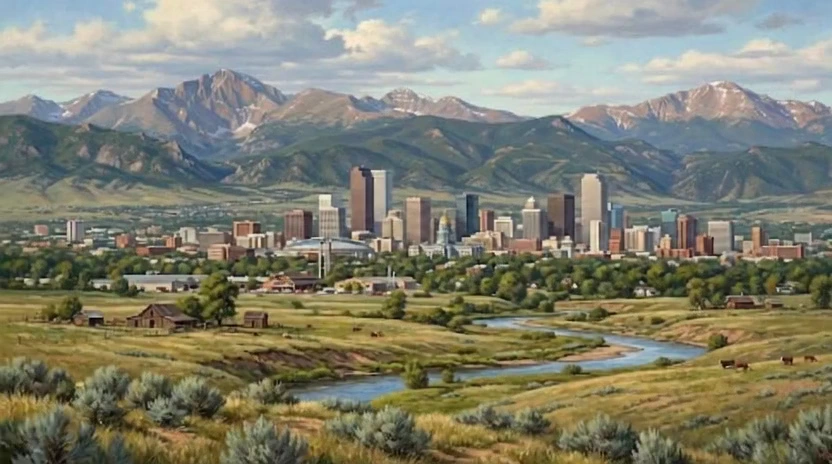

The city sits exactly where the Great Plains end and the Rocky Mountains begin, the transition so abrupt it looks like a mistake, like someone drew a line and said flat stops here, vertical starts now. Denver is at 5,280 feet, exactly one mile high, a fact the city announces with almost religious fervor, painting the step on the state capitol building, marking it on every piece of civic infrastructure, as if altitude were achievement rather than accident of geography.

The South Platte River runs through the city, though calling it a river requires generosity. Most of the year it's a creek, sometimes barely a trickle, the kind of waterway that in any humid climate would be called a drainage ditch. But this is the arid West, where water means everything, where the lack of it shaped history more than its presence. The city exists here not because the location was ideal but because gold was discovered in 1858 in the streams coming down from the mountains, and gold makes men ignore practicality. They called it Pike's Peak or Bust, and thousands came busting across the plains in wagons, most finding no gold, staying anyway because going back meant admitting failure.

The town that formed was makeshift and violent, a collection of tents and wooden buildings thrown up in the mudflats where Cherry Creek met the South Platte, rival town companies fighting over which settlement would be the settlement, claim-jumpers and con men and the occasional legitimate businessman trying to build something permanent. They named it Denver after James Denver, governor of Kansas Territory, attempting to curry favor, not knowing he'd already resigned by the time they used his name. He never visited. Never saw the mountains or the plain or the city that carries his name like an unreturned letter.

They called it Pike's Peak or Bust, and thousands came busting across the plains in wagons, most finding no gold, staying anyway because going back meant admitting failure.

The Railroad That Saved Itself

The railroad made Denver matter. When the transcontinental railroad bypassed the city in 1870, going through Cheyenne instead, Denver's boosters refused to accept irrelevance. They raised money and built their own spur line north to connect with the Union Pacific, then more lines west into the mountains to reach the silver mines in Leadville and Aspen. Denver became the hub, the place where ore and cattle and timber came down from the mountains to be processed and shipped east, the commercial center of the Rocky Mountain region by virtue of determination and strategic railroad building rather than geographic necessity.

The silver crash of 1893 should have killed the city. When silver was demonetized, the mining economy collapsed overnight, fortunes evaporated, banks failed, people left. But gold was discovered again, this time in Cripple Creek, and the cycle repeated—boom, wealth flowing into Denver, mansions built on Capitol Hill by mining magnates who never swung a pickaxe but owned the claims. The pattern was established: Denver as the place that processed mountain wealth, the civilized city where rough mountain money came to be laundered into respectability, where mine owners built opera houses and museums to prove that extraction could fund culture.

Denver as the place that processed mountain wealth, the civilized city where rough mountain money came to be laundered into respectability.

The oil came later, the 1970s energy boom when OPEC embargoes and rising prices made drilling profitable, when Denver became an energy town, corporate headquarters for oil and gas companies moving from Houston and Oklahoma City, geologists and engineers and landmen filling office towers downtown. The skyline rose in that decade—the cash register building, the Wells Fargo Center, towers with names that changed as companies merged or failed or relocated. The boom went bust in the mid-1980s when oil prices crashed, vacancy rates downtown hitting forty percent, construction cranes disappearing, the whole city suddenly too big for its economy.

The recovery came through diversification and the particular accident of being beautiful. The mountains are visible from everywhere, the Front Range rising abruptly fourteen thousand feet just west of the city, snow-capped most of the year, alpenglow turning them pink at sunset, a reminder that wilderness is not distant but immediate. This proximity to outdoor recreation—skiing an hour away, hiking and climbing and mountain biking accessible from the city—made Denver attractive to a particular demographic: educated, active, environmentally conscious, fleeing expensive coasts for affordable mountains. The city filled with Californians and Texans, tech workers and startup founders, breweries and bike lanes multiplying to accommodate them.

The Latest Legal Frontier

The legal marijuana arrived in 2014 when Colorado's voters decided prohibition was pointless and taxation was better. Dispensaries opened on every block, green crosses glowing like pharmacies, the whole industry springing up with remarkable speed. The tax revenue flowed to schools and infrastructure, the predicted social collapse never materialized, and Denver became a destination for weed tourism, bachelor parties and curious retirees showing up to legally buy products that would land them in jail two states over. The smell of cannabis hangs in certain neighborhoods, parks and concert venues, casual as cigarette smoke was in the 1970s.

The growth has been relentless, the population increasing by 100,000 in a decade, cranes dotting the skyline, apartments rising in every neighborhood, housing prices doubling and doubling again. The natives—people who grew up here, whose families go back generations—complain about the transplants, the traffic, the crowding, the way their affordable mountain city became expensive and congested. The "Native" bumper stickers appear on cars, a defensive marker of belonging, though everyone's ancestors came from somewhere else, the Arapaho and Cheyenne who actually belonged driven out in the Sand Creek Massacre of 1864, killed by Colorado militia who attacked a peaceful camp, murdered women and children, brought back body parts as trophies.

The homelessness is visible and worsening, tent encampments under freeway overpasses, along the South Platte trail, in parks downtown. The altitude and the winters kill people—hypothermia when temperatures drop, the thin air making health problems worse, the city's services overwhelmed by need and underfunded by voters who moved here for quality of life and resent visible poverty as aesthetic failure. The sweeps happen periodically, police clearing camps, bulldozers taking tents and possessions, the people displaced moving blocks away to start again.

The weather is schizophrenic, 300 days of sunshine advertised in every tourism brochure, but those other sixty-five days include blizzards that drop three feet of snow and close highways, hailstorms that shred crops and total cars, tornadoes spinning down from thunderheads, the whole range of meteorological violence compressed into a region where the mountains create their own weather. A day in March can be seventy degrees and sunny, then twenty-four hours later eighteen inches of snow, the locals claiming if you don't like the weather, wait fifteen minutes, advice that's actually true.

The sprawl is western and automotive, the city spreading north to Fort Collins, south to Colorado Springs, east into the plains in subdivisions that repeat endlessly, every exit off I-25 another cluster of chain restaurants and big box stores, housing developments named for the ranches they replaced—Prairie Vista, Mountain View Estates—selling a version of Colorado that exists primarily in marketing materials. The light rail expanded, sixteen lines now, an attempt to impose transit on a car-dependent city, used primarily by airport travelers and downtown workers, most residents still driving everywhere because distances are too great and frequencies too low.

REI is the cathedral, the flagship store in Denver drawing pilgrims who worship at the altar of gear.

The culture is outdoorsy to the point of parody, everyone in Patagonia fleeces and hiking boots even in office buildings, cars loaded with ski racks and bike racks, weekend plans revolving around which peak to summit or which trail to ride. REI is the cathedral, the flagship store in Denver drawing pilgrims who worship at the altar of gear, the conviction that the right equipment makes you legitimate, that outdoor recreation is not leisure but identity. The breweries number in the hundreds, craft beer the civic beverage, taprooms packed on weekday afternoons with people who claim to work remotely but mostly seem to drink IPAs and talk about powder days.

The politics are blue in the city, purple in the suburbs, the Front Range corridor increasingly Democratic while the Western Slope and the plains remain Republican, the divide less urban-rural than mountain-plain, people oriented toward Denver versus people oriented away from it. The state legalized marijuana, allows abortion, passed gun restrictions, policies that make rural Colorado furious, the occasional talk of splitting the state reflecting the gap between Denver's values and everyone else's.

Alpenglow and Uncertainty

To live in Denver is to live in a place defined by proximity to beauty that most people access primarily on weekends. The mountains are there, always visible, a promise and a reproach, a reminder that the city is tolerated by the landscape rather than emerging from it. The air is thin enough that visitors gasp climbing stairs, that alcohol hits harder, that athletes train here for the altitude advantage. The sun is intense at this elevation, skin cancer rates high, everyone squinting against brightness that feels aggressive.

The city persists in a place where water is scarce and getting scarcer, where the Colorado River basin is overallocated, where lawns are slowly being replaced by xeriscaping, where the growth everyone celebrates depends on resources that climate change is making unreliable. The ski resorts report shorter seasons, the snowpack declining, the West drying out in ways that make Denver's future uncertain in ways the boosters don't mention in their pitches.

But the mountains are still there, turning pink in the alpenglow, the sun setting behind them every evening in displays that stop traffic, that make people pull over to take photos that never capture what it actually looks like. The city sits at their feet, one mile high, still rising, still growing, still convinced that altitude equals destiny, that being near the mountains makes you worthy of them, that the West's promises still hold despite evidence accumulating like snow before an avalanche that the agreements underlying everything—about water, about growth, about limitless expansion—were always temporary, always subject to revision by forces larger than civic ambition or real estate markets or the accumulated will of people who came here because the mountains were beautiful and stayed because staying felt like winning.